The Strife of Camlann is still in editing mode at the publisher, and I’ve started working on Three Wicked Revelations, the third book in The Arthurian Age series. Another effect of finishing a book is that I’m suddenly freed up to tackle the honey-do list. It just so happened that in the process of doing one of those items, I was inspired to write this article.

We’re putting a little screened-in porch off the bedroom so we can enjoy Maine’s lovely 6-week summer without going mad from swarming pests. While removing a window to put in a door, we had to cut out some of the existing wall structure. And in doing so, we pulled up a board and found this hidden beneath it.

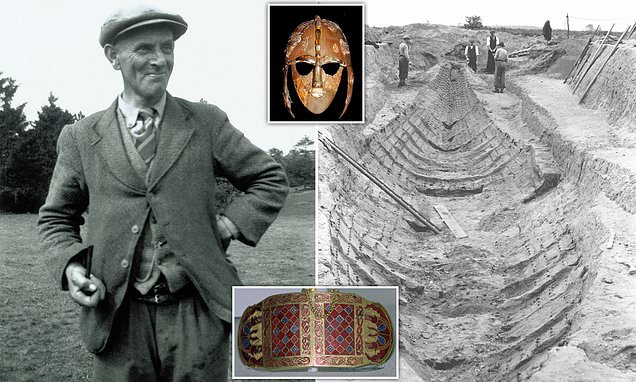

Yes, a penny. I mean… A penny! Not terribly exciting, I know, but I instantly became Basil Brown from “The Dig“. My research into The Retreat to Avalon made me delve into all sorts of arcane subjects, and finding that penny made me recall my childhood dream of being an archaeologist. It was second behind astronaut, and obviously I missed both marks by a long shot.

In any event, writing historical fiction lets me dig into the past and experience the ancient world in my mind, and hopefully help others to do the same. To do that effectively, I’ve had to learn a bit about a lot of subjects. Archeology is an important one because of the many details we can learn from the remains of human activity, and coins hold a special place in that science.

The earliest coins we have found are in western Turkey from around the 8th century, B.C. They were made of electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver, and used in religious settings. It would take a while before they became commonly used in trade. According to legend (often having roots in history), coins were invented by Hermodice II after she married King Midas, a likely historical king of Phrygia, remembered for the curse of The Golden Touch.

Most of the coins found from ancient times are small and made from copper alloys. Some were lost, much as we lose pocket change today, or used as tokens, like the custom of wishing wells. The Greeks placed a coin under the tongue of their dead to pay Charon to ferry the soul of the departed across the River Styx to the realm of Hades.

Unlike the gold, silver, bronze and other coins of the ancients, our coins, today, are generally larger, and rarely contain any precious metals. It’s very much a simplification, but generally speaking, a small bronze coin would be worth a loaf of bread, a silver coin or two would be a worker’s daily wages, and a gold coin would purchase a horse. A great article with more detail may be found here.

One of the great things about coins is that they usually help us to know the general dates of when something happened. Coins often have dates on them, and even if they don’t, coins often changed details from year to year, such as to show different rulers or messages.

Archeologists use stratigraphy to analyze the layers of earth and debris that build up over time. This can help identify the time frame of events and artifacts when used in conjunction with other data. Coins are excellent tools in this case. When they appear in a place that was protected from contamination from later or earlier periods, it helps the archaeologist date that layer, and the other items around it. At the very least, the archaeologist knows that the layer cannot be from a time any earlier than oldest coin found.

So I was interested to see the date on this penny. My house was built somewhere between 1977 and 1979. This penny was minted in 1972. You could still buy a piece of “penny-candy” with it back then. It travelled from hand to hand, pocket to pocket, for at least five years before a carpenter dropped it on the footer beam, raised the wall, and nailed it into place over the penny, for me to find more than 40 years later.

Thanks for coming by. I hope you’ll check out The Retreat to Avalon and that it will make you eager to read the sequel, The Strife of Camlann, because in the next book, Three Wicked Revelations, we’re going to back to watch the rise of Arthur and learn what brought about many later events.

Coins are fascinating and often used as propaganda. There is one showing a Roman emperor taking back Britain after the Carausius separation and another with Zenobia claiming parity with Rome for Palmyra. My favourite is a British coin with a charioteer holding aloft a miniature ship. About the time of the invasion by Julius Caesar. It has been interpreted as a chariot born British coast watch. Worked when Julius arrived and was met by the British forces.

What better way of getting your name and message out than on the money people use?